Meet the ancestors - The Range Rover at 50

“It is a car for the man who has no time to attend to carpets, walnut facings and luxurious hide upholstery.”

No, not the Suzuki Jimny. Not even the Dacia Duster. Believe it or not, those words – from Autocar magazine in the early 1970s – describe a Range Rover. And it was true: when they first appeared 50 years ago, Range Rovers had an austere cabin of plastic, vinyl and painted steel. An upgrade from PVC to brushed nylon seats was as indulgent as it got for the first decade.

Advertisement

Advertisement

So, while those early cars were barely ritzier than the back of a riot van, do they have anything at all in common with 2020’s decadent Range Rovers? We’ve gathered one of the 28 pre-production vehicles from 1970 and a current SDV8 Vogue to find out.

The older car marks the final stage in the birth of Range Rover. The idea was to build a sort of more civilised Land Rover to grab a slice of the emerging market for American-style ‘leisure vehicles’. A string of seven prototypes evolved from a chunky, van-like brute with mostly Land Rover hardware to the svelte form we now recognise as the first-generation Range Rover, packed with modern kit including disc brakes, a new four-wheel-drive system, a self-levelling rear end and coil suspension in place of traditional leaf springs.

It was those coil springs – derived from Rover’s saloon-car range – that blessed the Range Rover with its party trick of enormous wheel travel, helping it soak up lumps and bumps like no off-roader before.

But how best to publicly demonstrate that skill? As it happened, the UK’s first-ever "hillrally" – a timed cross-country dash up hill and down dale – was slated for May 1971 in Mid Wales, and Rover’s top brass wanted to win it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

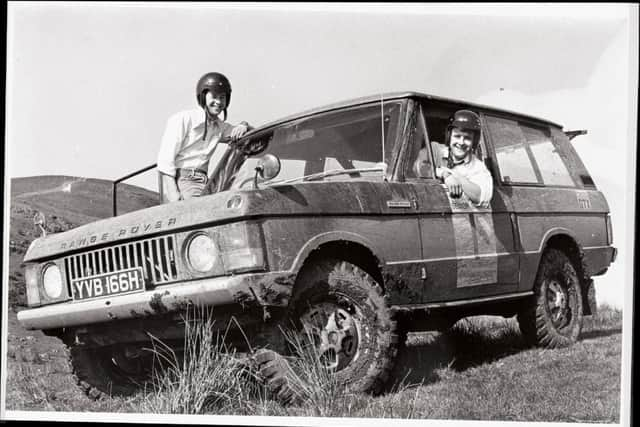

With its development duties completed, this very car – YVB 166H (aka ‘166’) – was picked for the task, with one of the Range Rover’s original engineers, Roger Crathorne, doing the driving. Against US Army Jeeps, Toyota Land Cruisers, Austin Champs and plenty of Land Rovers, it was a revelation, the brawny, 156bhp 3.5-litre V8 sending it languidly bounding over terrain that had the others bucking like mad.

As Crathorne describes it: “There were thousands watching and they were all standing on the track, trying to force you into a bog. I told [navigator] ‘Taff’ Evans to keep on the horn, because we’re going through them. We were going 60-70mph off-road, which is a bit stupid, really. At one stage I actually overtook the pace car.”

After two days of competition, they duly delivered the trophy back to HQ.

Crathorne later used the car as a family hack, but now it belongs to Richard Beddall, trustee of the Dunsfold Collection of historic Land Rovers. He rescued it from a shipping container in 2012 and restored it complete with 1971 hillrally livery. He’s even got the hammer Crathorne used to straighten wheel rims bashed in battle.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Inside 166’s wizened but workmanlike cabin, there’s all-round light and visibility to rival a Victorian bandstand, contrasting with the modern Vogue’s thick-pillared, indulgently trimmed cocoon. The all-aluminium V8 – originally sourced from General Motors for Rover saloons – gives off a charming metallic churn as we pull away and I get my first withering armful of 50-year-old unassisted steering.

It slacks off as I make the lengthy shifts into second, then third, and we’re soon loping along in comfort. Throttle response and stopping power alike impress: I can see how Crathorne used the car for trans-European family holidays. It was developed to cruise fully laden at over 90mph, after all.

Alongside the four-speed gearbox’s beanpole lever is a tangle of other manually operated sticks and stops: centre differential lock, dual-range selector, custom-fitted overdrive and handbrake. Not one appears in the new car, all having been subsumed by electronics. Current Range Rovers can even be specced with an off-road cruise control, automatically keeping a set speed over whatever surface you throw at it.

Such advancements pepper the model’s history, though the greatest leaps belong to the first-generation’s remarkable 26-year innings that included the addition of power steering, automatic gearbox, fuel injection, diesel power, ABS, traction control and electronically controlled air suspension.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Subsequent versions were bigger and brasher. The ‘P38a’ (1994-2001) introduced electronic range selection and unabashed excess (see the £100,000 ‘Linley’ edition), while the L322 (2002-2012) ditched the traditional ladder-frame chassis in favour of a monocoque and added terrain-specific traction programmes. Electrically assisted steering, active roll control and hybrid drive all debuted in the current ‘L405’, launched in 2012.

Of course, there’s a chasm between the dynamics of our two cars. The L405 operates with a glossy aloofness, giving maximum performance for minimum input, with the minimum of fuss. Where Crathorne expertly toiled at the controls of 166 as it grappled and galloped through those Welsh mountains, for example, an off-roading novice could arguably go quicker in the current car without spilling their coffee. It has almost thrice the torque and its clever electronics can call upon dual range, locking centre and rear differentials, adjustable air springs for towering ground clearance and wading ability of nearly a metre.

It’s true that today’s Range Rover does things very differently from the original. But what it does has barely changed. It carries several people – and their stuff – in comfort. It accelerates and handles beyond its bulk. And don’t let the urban image fool you, because it tackles off-road challenges as well as anything else Land Rover makes; carpet, walnut, leather and all.

Getting Range Rover off the ground - three earlier attempts to civilise Land Rover

Land Rover Station Wagon

Introduced just after Land Rover’s 1948 debut and borrowing the ‘station wagon’ label from America, this multi-purpose 4x4 people-carrier was outsourced to coachbuilder Tickford, who fitted a mahogany-framed aluminium body to a beefed-up Land Rover base. It had three front seats, four more in the back and the split rear tailgate since featured on all Range Rovers. A steep price meant only 641 were made.

Road Rover Series I Prototype

Advertisement

Advertisement

Between 1952 and 1955, 12 of these two-door prototypes were built combining Land Rover’s simple, upright styling, aluminium body and 2.0-litre petrol engine with chassis sourced from the Rover P4 saloon. They had coil springs, but only at the front, and while four-wheel drive had been planned, most were rear-drive. It was nicknamed ‘Greenhouse’ for its basic design, but was upholstered with carpets – a luxury unknown to Land Rover owners.

Road Rover Series II Prototype

Lower, longer and with Americanised styling, nine more Road Rover prototypes were built between 1956 and 1958 using parts from the P5 saloon. Its two front seats and three-person rear bench offered a car-like layout, and like the initial Range Rover design, the production version was to have a straight-six engine. This weather-ravaged example was secretly tested by Rover chairman Spencer Wilks on his Islay estate – as was the very first Range Rover prototype in 1967.

Toy story

The second Road Rover came so close to production that Corgi Toys had secretly developed a scale model. It was so hush-hush that the embossing plates for the underside were made in two halves, preventing the full name being seen. One said ‘Rover 90’, the other, ‘Road Hawk’. The ‘90’ and ‘Hawk’ would be machined off and the pads married up to read ‘Road Rover’.